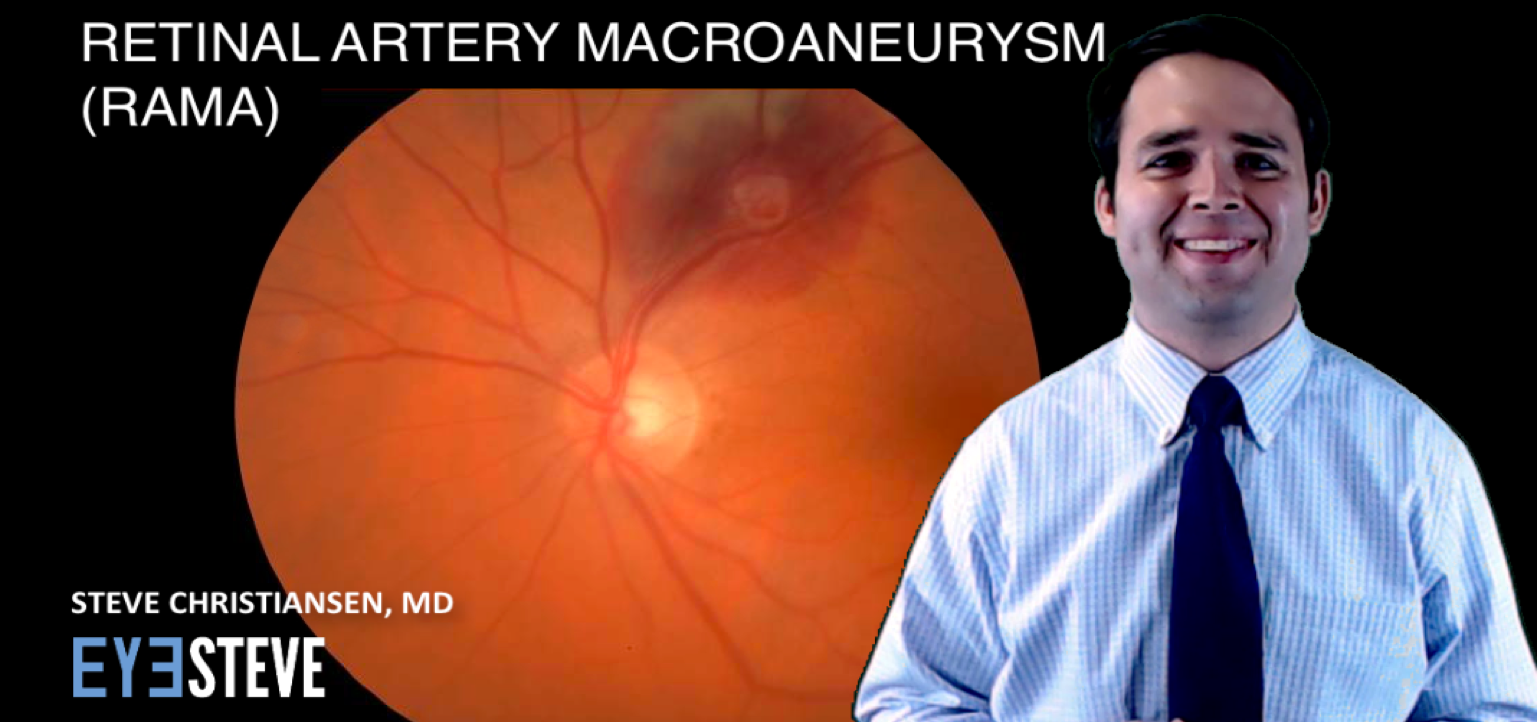

In this post (and video!) I briefly discuss the key features, diagnosis, and treatment of retinal artery macroaneurysms, more commonly known as RAMA.

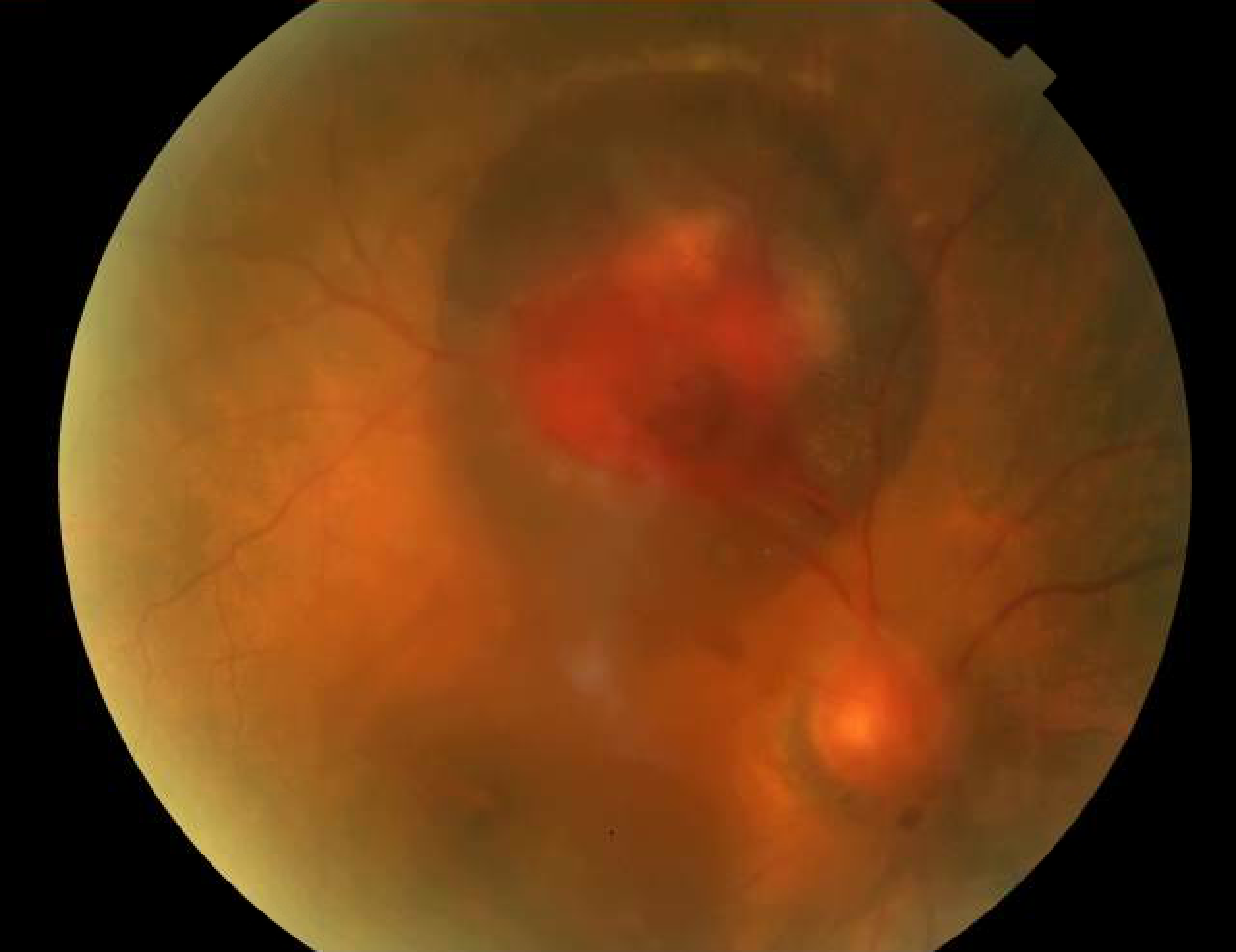

The clinical picture in this vignette is of an 80 year-old hypertensive Caucasian woman who presented to our urgent clinic with new-onset floaters. Her vision was 20/250 in the left eye, and the anterior segment examination was normal.

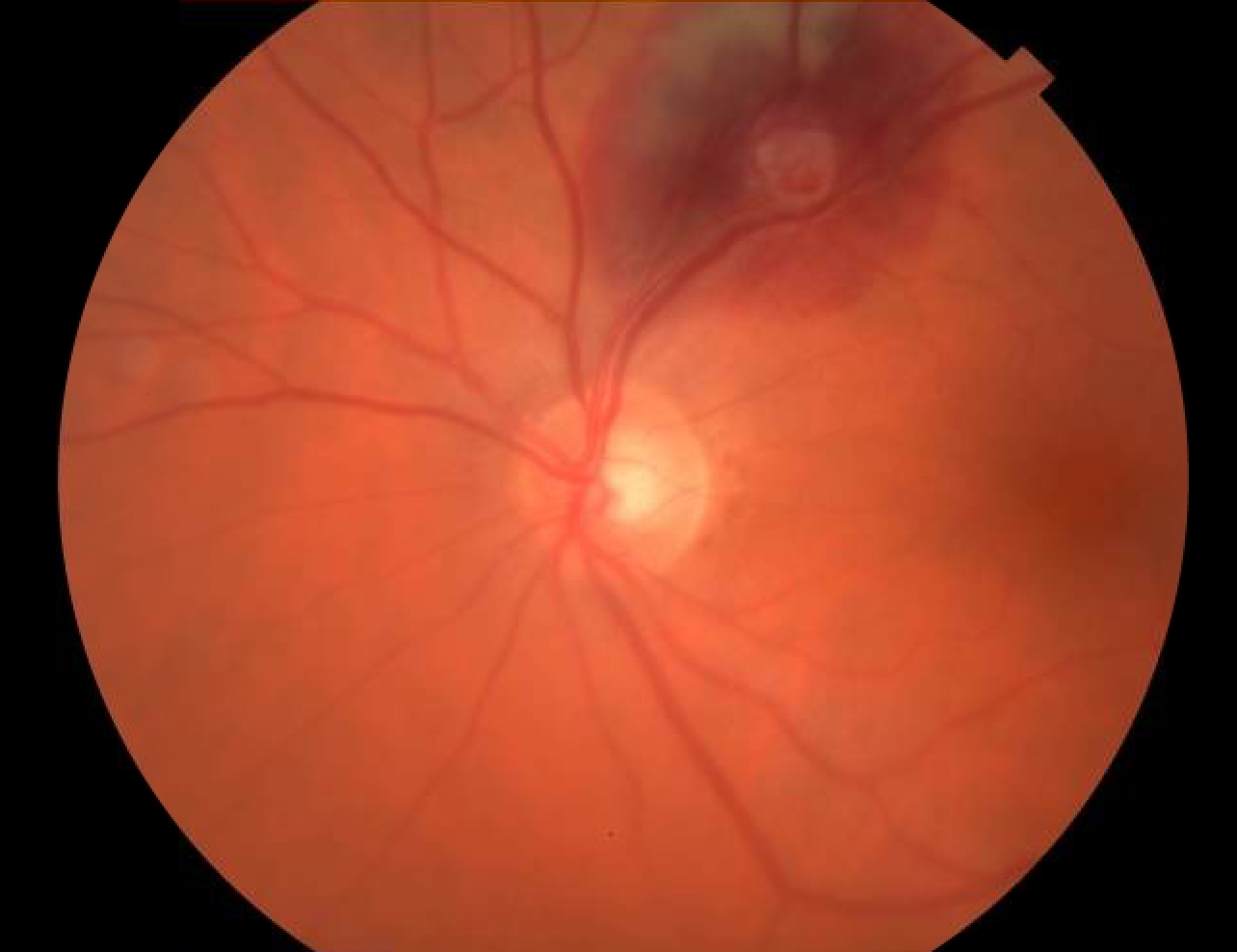

This is a fundus photo of the left eye, which shows a slightly hazy view due to vitreous hemorrhage. Along the superior vascular arcade you see a discrete area of deep, subretinal hemorrhage with a white spot in the center, and perhaps some pre-retinal hemorrhage just anterior to this white area. Based on her history and these exam findings, it was suspected that she had a retinal artery macroaneurysm.

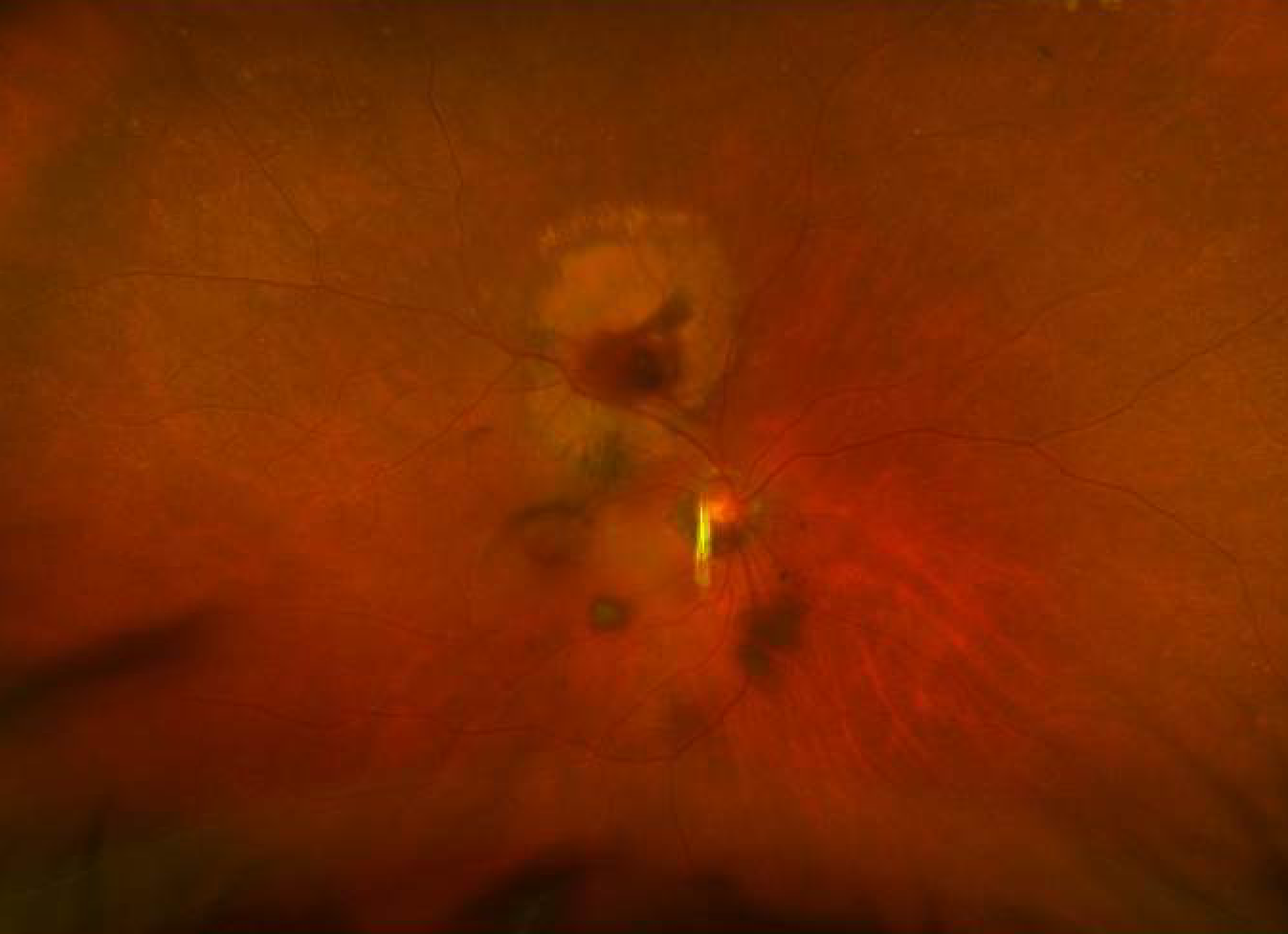

She returned two and a half months later, and her vision had returned to 20/20, with resolution of the vitreous and subretinal hemorrhage, but persistence of the yellowish macroaneurysm.

Let’s review some important features of retinal artery macroaneurysms.

RAMAs are round dilations, or aneurysms, of retinal arterioles. They most commonly affect women in their sixth decade of life, or later. They typically occur in just one eye and within the first three branches of the superotemporal retinal arteriole. The pathogenesis is not known, though one theory is that systemic arteriosclerosis causes fibrosis within the wall of the vessel. The resulting decreased elasticity, coupled with systemic hypertension leads to development of the aneurysm.

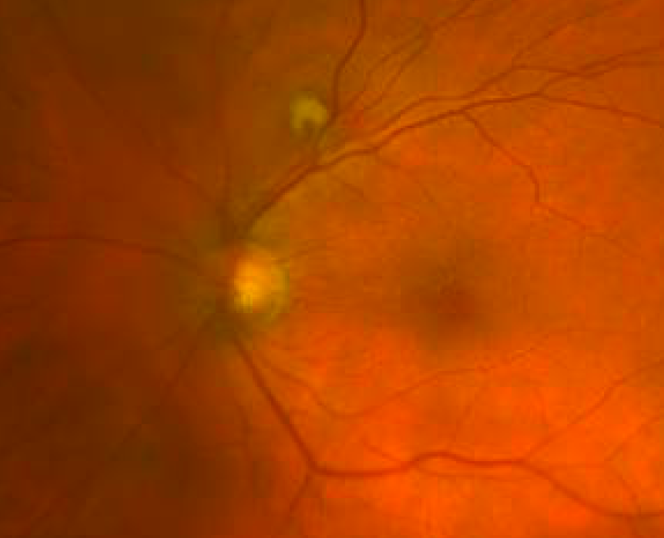

If the macroaneurysm ruptures, hemorrhage can be seen at multiple levels, as can be seen in this photo of a different patient, in this case an 88 year-old, hypertensive woman who I also believed had a RAMA. You can see that the view is hazy due to dispersed vitreous hemorrhage. You can also see an area of likely preretinal hemorrhage centrally, and surrounding deep, subretinal hemorrhage.

If the macroaneurysm ruptures, hemorrhage can be seen at multiple levels, as can be seen in this photo of a different patient, in this case an 88 year-old, hypertensive woman who I also believed had a RAMA. You can see that the view is hazy due to dispersed vitreous hemorrhage. You can also see an area of likely preretinal hemorrhage centrally, and surrounding deep, subretinal hemorrhage.

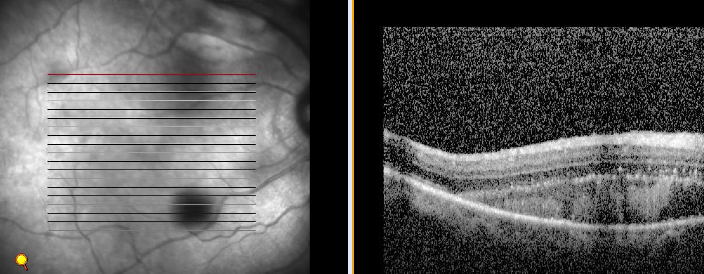

When this patient returned three weeks later, much of the vitreous and subretinal hemorrhage had resolved, but significant exudate remained, with subretinal fluid now involving the macula, which you can see on this OCT.

When this patient returned three weeks later, much of the vitreous and subretinal hemorrhage had resolved, but significant exudate remained, with subretinal fluid now involving the macula, which you can see on this OCT.

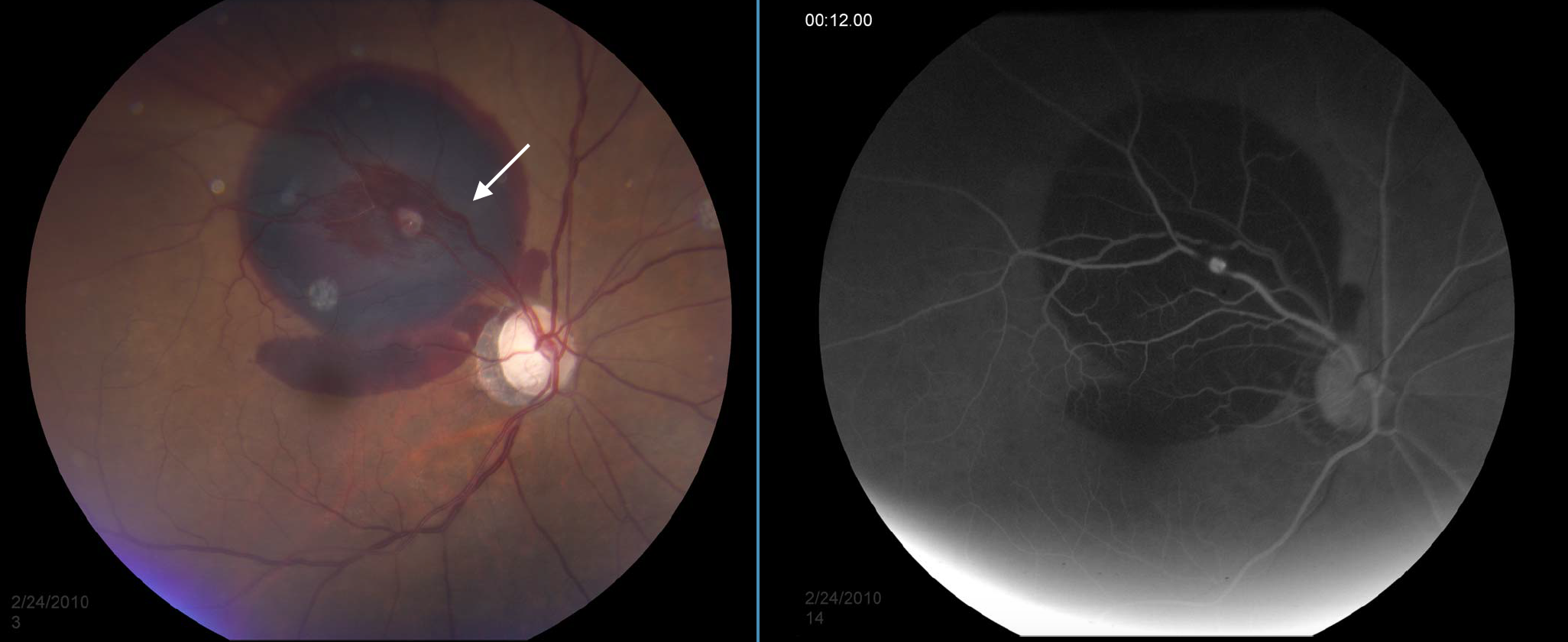

A fluorescein angiogram was performed, but unfortunately did not clearly photograph the macroaneurysm. Let me show you some wonderful FA photos of RAMA from the University of Iowa. Here you see a fundus photo of the right eye showing a large area of subretinal hemorrhage, with hemorrhage extending into the macula, and a small amount of preretinal hemorrhage. Note the white spot along the superotemporal artery which corresponds to the hyperfluorescent lesion in the angiogram.

A fluorescein angiogram was performed, but unfortunately did not clearly photograph the macroaneurysm. Let me show you some wonderful FA photos of RAMA from the University of Iowa. Here you see a fundus photo of the right eye showing a large area of subretinal hemorrhage, with hemorrhage extending into the macula, and a small amount of preretinal hemorrhage. Note the white spot along the superotemporal artery which corresponds to the hyperfluorescent lesion in the angiogram.

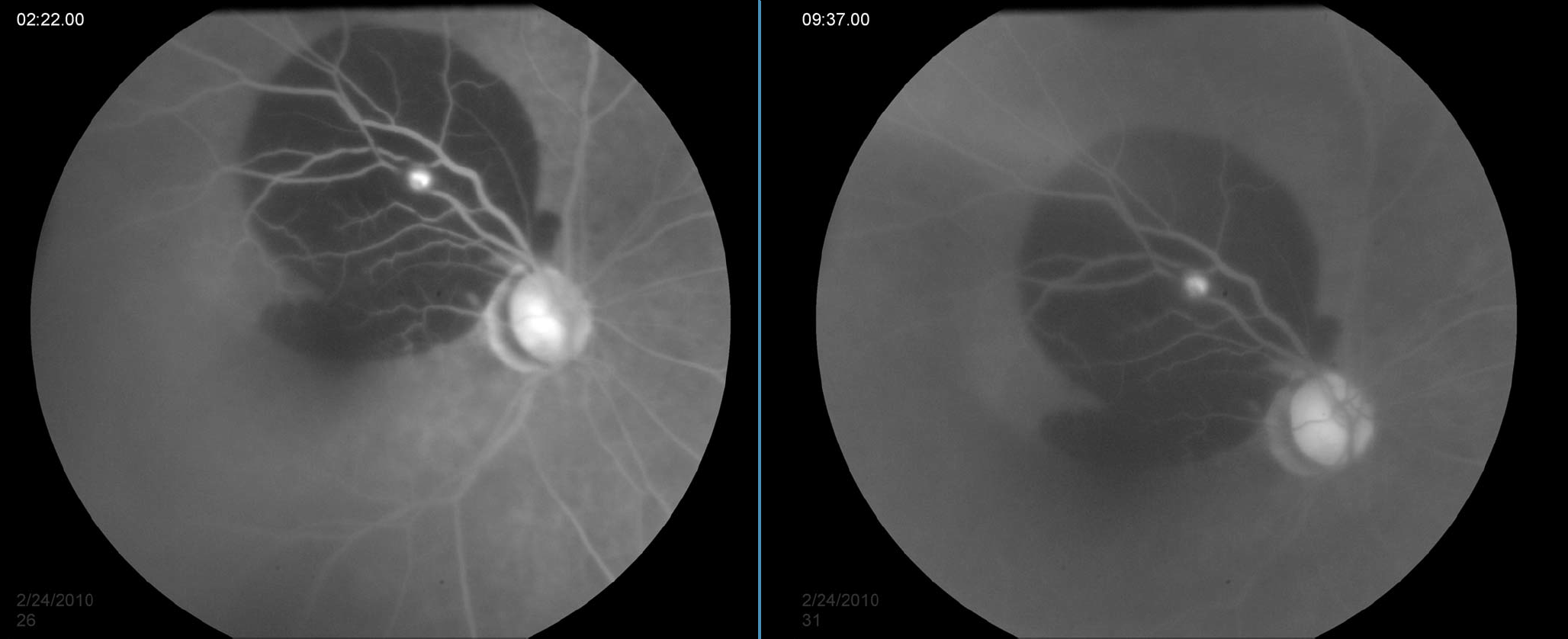

Here, in the midvenous phase, there is increased hyperfluorescence, which persists in the late phase seen also seen below.

Because the majority of macroaneurysms involute spontaneously, most patients can be safely observed without treatment, though hypertension and other vascular risk factors should be controlled as much as possible. Treatment options include laser photocoagulation or, especially in recent years, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections for macula-involving subretinal fluid.

In summary, retinal artery macroaneurysms typically occur in elderly women with systemic hypertension, and present with a painless decrease in vision in one eye. Examination demonstrates hemorrhage at multiple levels, often with a focal, white or yellow lesion at the center of the hemorrhage, most commonly within the first few branches of the superotemporal arteriole. RAMA can typically be observed, but anti-VEGF or laser could also be considered.