My childhood sports hero was John Stockton. His poster was in my room, his trading card in my wallet, and his signature #12 on my uniform for every sport I played. When asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, what was my reply? I was going to be in the NBA.

My dream of becoming a professional athlete became an even loftier and far-fetched wish when I was just 10 years old and had trouble seeing the chalkboard. Soon enough, after a visit to the eye doctor, I was one of the first kids my age to have glasses. I was the nerdy kid playing in city-wide basketball leagues with the 1990’s “chums” keeping my glasses on my head and hoping to avoid errant passes smashing my lens frames into my face.

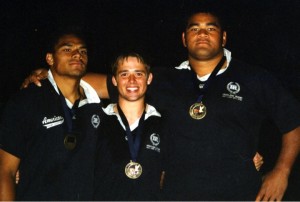

Years later, I was one of just a few teammates asked to give the college rugby athletic trainers an “extra pair of contacts” just in case a contact lens popped out of my eye in a scrum or when being smashed by an opposing player, which would have left me the nearsighted scrumhalf trying to lead my team down the field unable to see where I was passing the ball or which team I was on. Fortunately, several of my teammates, including current and past NFL stars, Haloti Ngata and Fui Vakapuna, were of such gigantic stature that I could recognize them with or without contacts.

So why don’t you hear about more professional athletes having contact lens issues during games?

It’s because professional athletes have superhuman vision. No joke.

In 2009-2010, Michael Peters, O.D., team optometrist for the NHL’s Carolina Hurricanes, read a study reporting that 59% of individuals age 18-34 require contacts, glasses, or refractive surgery. He had noticed, however, that this high percentage was much different than he had witnessed while working with professional athletes for over a dozen years. He then sent a questionnaire to athletic trainers for all the teams in the NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL asking how many of their team’s athletes actually needed glasses or contacts or had had refractive surgery. The results of his survey were shocking. Here are the percentage of professional athletes that needed vision correction:

• 17.1 percent of NFL players

• 16 percent of NBA players

• 29.6 percent of MLB players

• 20.2 percent of NHL players

Just to put this in perspective, if you and I were to get 22 of our friends in the ages 18-34 together for a pick-up football game, thirteen of them would be wearing contacts, glasses, or would have had refractive surgery to correct their vision. How does that compare to the 22 NFL players you will watch playing on the field in the Superbowl? Four. That’s right, just 4/22 NFL players require vision correction compared to 13/22 of your friends in the same age group as the professional athletes playing with you in the front yard. According to Dr. Peters, “The eyes of professional athletes are substantially better than the eyes of the average population in the same age group. You really do have to see to play. The amount of detail a player can see in front of him determines how quickly he reads a defensive formation, or where a pass is headed.”

According to Peter Kaiser, MD, an ophthalmologist at the Clevaland Clinic who works with the Cleveland Browns, “Even high draft picks can make it to their initial team medical exam with an undiagnosed or poorly corrected vision problem. If they’re not in a marquee position, it may not be a big deal, but for a wide receiver or a safety, it might factor into the team’s decision. If the eye problem can’t be fixed, the player’s career may be in jeopardy.”

As it turns out, professional athletes have superior vision beyond just not needing contacts or glasses. According to Dr. Peters, the peripheral vision of professional athletes is wider, the muscles of their eyes move better, their depth perception is better, their ability to change focus is faster, and their eye-hand and hand-eye-body coordination is better. In a 1997 study, the vision reaction time of 92 professional baseball players who played in at least 100 games was found to be associated with the player’s batting average (p = 0.017). These results were similar to those of a 1996 study of 387 professional baseball players which found significantly better mean visual acuity, distance stereoacuity, and contrast sensitivity than those of the general population as well as statistically significant differences in steropsis and contrast sensitivity between major and minor league players.

Can something be done to improve the vision of an athlete hoping to improve their chances of making it in the big leagues or gain an edge over the competition? Many sports vision centers provide vision training to athletes with exercises to improve tracking, target localization, eye-hand/eye-foot coordination, vision reaction time, depth perception, and other eye exercises. Multiple studies have been performed to analyze similar vision training techniques. In 1997, the Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus performed a review of the published literature on vision training and found no clear scientific evidence published in the mainstream literature supporting the use of eye exercises, and their use therefore remains controversial. Athletes have continue to seek a competitive edge, and in recent years use of soft contact lenses among professional athletes has increased, with the thought that contact lenses may improve contrast sensitivity, thus improving the ability to pick out the fast-approaching ball coming at them when mixed with the many contrasting colors and brightness of the crowd, lights, and other distractions of professional sports. According to a 2012 NBC news story, the color of the tinted contact lens that is used depends on the sport being played, with football players wearing blue, golfers green, and baseball players amber. Why amber for baseball? Manufacturers claim the amber-tinted lens provides a filter which enhances the ability for batters to see the stiches on the baseball, enabling faster determination of pitch type and location. A 2007 study published in Optometry examined the contrast sensitivity of 35 collegiate or professional athletes when wearing either an amber-tinged or clear soft contact lens and found a statistically significant effect on contrast sensitivity when wearing a sport-tinted contact lens, though the authors doubted the clinical significance of such an effect. A handful of athletes have even been found to wear the soft contact lenses on game day, including Santonio Holmes of the New York Jets and Bryce Harper of the Washington Nationals.

Many other athletes have chosen laser refractive surgery as their preferred method of vision correction, including Tiger Woods, Troy Aikman, Mark Maddox, and Amare Stoudemire, among many others. In February of 2012, after a rookie season where he caught just three catches for 31 yards, Seattle Seahawks wide receiver Jermaine Kearse had LASIK surgery, and in the 2013 regular season had a breakout year with 22 catches for 346 yards and 4 touchdowns. Even outspoken teammate Richard Sherman has noticed a difference in Kearse’s ability to see the ball, saying, “He’s catching the ball at its highest point. He’s attacking it. It seems like he’s able to locate it a little better, a little quicker.” Other athletes, such as Gary Player, winner of nine major golf championships, have chosen multi-focal lenses for their refractive correction. Discussing the impact of multi-focal lenses on his golf game, Player has said, “I’ve noticed a massive difference. I can read the line of the putt so clearly – I am much more decisive in club selection. I can even read the scorecard.”

In recent months I have been reading the autobiography of my hero, John Stockton, reflecting on my dream of one-day playing in the NBA. If only someone could have told me my poor vision may have been a poor prognostic sign for a future as a professional athlete – I could have avoided the chums, the polarized lenses, and the bruises from my glasses smashing my cheekbones. Then again, being the dreamer I am, I would likely have been certain that I would beat the odds, I would be one of the handful of professional athletes that do still need to wear contacts or glasses. I would have been the nearsighted human among superhumans.

[…] Don’t believe that elite athletes with vision problems soar to the top of their chosen game wearing contact lenses? How about Cristiano Ronaldo. And Novak Djokovic. And about 20 percent of every player on every professional sports field in the world. […]

Just wanted to let you know I found this article really interesting and informative. By the way, I am still one of those poor vision kids hoping against all odds to make it against the superhumans!! 🙂 Good luck with ophthalmology and congrats on finishing med school (where did you go?) Hope to see you continue writing in the future…it is an excellent way to keep your mind of work.

1. That is a sweeeeeeet photo of you and Fui/Haloti.

2. The AAPOS, as you mentioned in your article, has long decried the practice of vision therapy as lacking in supportive evidence. Vision therapy typically is multiple thousands of dollars out of pocket and offered by a few optometrists to children with strabismus. I haven’t heard of it being used for athletic training before. Interesting.

3. I’ve wanted to work in a “famous people with eye conditions” into a morning rounds. Amar’e had an RD a few years ago. Max Scherzer has crazy heterochromia. Tony Parker reported he suffered a “scratched retina” during a basketball game…maybe the French words for retina and cornea are really similar.

4. Can’t wait to get you out here!

Matt,

Thanks for your comments and for the additional info on the AAPOS and reinforcement of vision therapy as lacking supportive evidence. As far as its use in athletic training goes, do a quick google search on the topic and you will see several vision centers advertising vision therapy for athletes. Like you (and the AAPOS apparently), I am skeptical of its benefit for strabismus, though I do also wonder about its use or benefit in athletes. The “evidence” supporting its use is likely anecdotal, which is, unfortunately, all many folks need to open their wallets and drop thousands to increase their child’s chances of making it to the big leagues. If I can help at all with your “famous-people with eye conditions” morning rounds, let me know! I’m sure such a video/slideshow of the morning rounds or of the content covered in such a rounds would generate substantial interest within social media, and would also increase exposure for screening, diagnosis, and treatment for such conditions. Fantastic idea!