All I remember is sprinting across the rugby field at full speed to tackle a runner charging in to score. From what others later told me, the opposing player’s knee struck my head as I went in for the tackle and I was knocked unconscious, speaking “gibberish” and being quite disoriented when I woke up, surrounded by teammates, coaches, and medical staff. Fortunately, the athletic trainer for my Highland Rugby team was well-trained in concussion screening and had even published research on the hidden epidemic of concussions in rugby, and recognized that my disorientation and inability to remember three (or was it four? or five?) words just minutes later were positive signs of a traumatic brain injury (TBI), and I was kept out of the remainder of the game. The concern over a possible concussion prompted a trip to the Emergency Department, and though a head CT was negative for structural abnormalities, I was presumptively diagnosed with my first concussion. The ED physician made the astute comment (which I imagine had something to do with my 5’8″ 165 lb frame) that a professional rugby career was likely not in my future, and that I should consider other career goals. Years later, I am grateful to not have experience sequelae of concussions, and am now able to applaud and further research, athletic, and industry efforts to improve concussion screening.

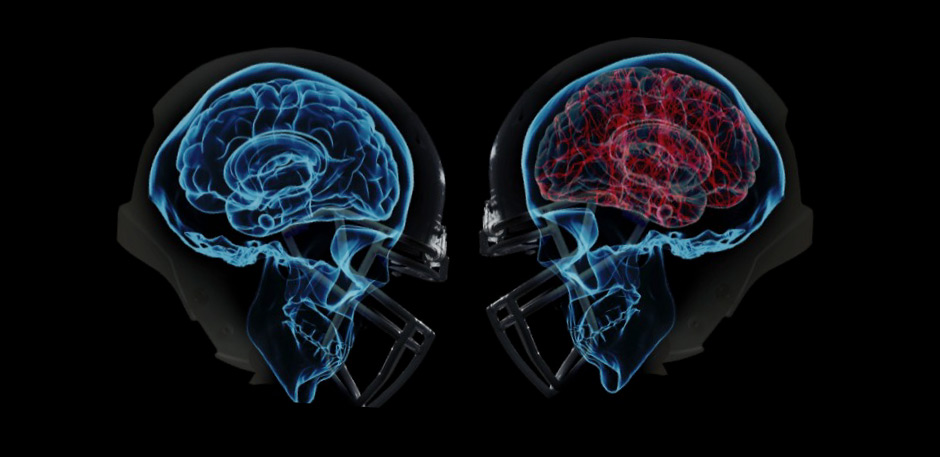

Traumatic brain injury in athletics has become THE main sports-medicine related topic in recent years, as former athletes have volunteered to undergo post-mortem autopsy testing to assess for brain damage suffered from sports-related trauma. New data from the nation’s largest brain bank focused on traumatic brain injury has found evidence of a degenerative brain disease in 76 of the 79 former players examined, causing the NFL and other professional sports to come under public and legal scrutiny as players allege the NFL minimized potential risks or did not make sufficient effort to protect players from head trauma. In 2013, PBS Frontline ran the story League of Denial: The NFL’s Concussion Crisis, and tracks the number of concussions diagnosed among NFL athletes, even breaking down the number of concussions by position. The NFL has repeatedly revised its concussion protocol, and now requires athletes to undergo in-depth medical evaluations including offseason baseline neuropsychiatric testing, medical history and symptom documentation, and strict physical exam requirements. Recognizing that players may not be the best historians and may be biased toward not reporting symptoms to avoid being sidelined with a possibly career-ending injury, the NFL’s concussion protocol includes monitoring of players on the field and on the sideline by the team’s medical staff, the officiating crew, and a specialized observer up in the booth seated next to the replay official and with the assistance of replay cameras that show every angle of every play.

Unfortunately, on-the-field hits that cause concussions are not always easily recognizable – this I know from personal experience. Less than a year after my first concussion on the rugby field, I was playing free safety for my high school football team, and dove for an interception along the sideline. I wasn’t struck by an opponent and didn’t suffer an obvious blow to the head, but when I got up I was disoriented and again failed the sideline concussion screening, being diagnosed with a second concussion. As noted in a recent Bleacher Report article, one of the major problems with concussions is that they’re not always visible. A player may appear normal but still have suffered a TBI such as a concussion. Subconcussive impacts take a toll that only shows up in advanced tests and brain damage down the line. The ability to effectively screen athletes for concussions represents a current need within sports medicine, and one which may have great impact for athletes in the future.

Researchers, physicians, and industry leaders recognize this need for improved concussion screening tools, demonstrated by a recent study published Jan 29, 2015 in the Journal of Neurotrauma in which researchers describe a new screening tool that tracks abnormal eye movements in the assessment of concussions and other traumatic brain injuries.

Here are a few highlights of the study:

Introduction:

- Disconjugate eye movements (where horizontal eye movements are not similar between the two eyes) have been associated with traumatic brain injury since ancient times, and ocular motility dysfunction may be present in up to 90% of patients with concussion or blast injury, suggesting motility evaluations may serve as a sensitive screening for concussions.

Methods:

- Researchers developed an algorithm for assessing the X and Y coordinates of the right and left pupil movements while subjects watched 200 seconds of a short clip from a music video and tested 75 trauma subjects and 64 controls to assess whether eye tracking might reveal disconjugate gaze associated with both structural brain injury and concussion.

- The 200 seconds of video that testing subjects watched and during which eye movements were analyzed were music videos such as Shakira’s “Waka-Waka“, K’naan’s “Wavin’ Flag“, Under the Sea from the Little Mermaid, “I Just Can’t Wait to be King” from the Lion King, Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror” or Shankar Ehsan Loy’s “Bhumbroo.”

Results:

- 5/5 measures of horizontal disconjugacy were increased in patients with positive head CT findings (hemorrhage, contusion, or skull fracture) and in those with a negative head CT (without CT evidence of structural damage) relative to non-injured control subjects. Linear regression analysis of all 75 trauma patients demonstrated that three metrics for horizontal disconjugacy positively correlated with total Standardized Assessment of Concussion (SAC) score, and that abnormal eye tracking metrics improved over time.

The “so-what” conclusions:

- Current concussion screening of disconjugate eye movements is based on the testing subject following the examiner’s finger in various directions, which is highly subjective and in all likelihood is poorly sensitive as a screening tool except in the most significant injuries. As stated by Richard G. Ellenbogen, MD, co-chair of the Head, Neck and Spine Committee of the NFL, this new method is “simple, non-invasive, reproducible and easy to perform on the sidelines or in the field. It provides a simple and elegant method of being able to assess the functional deficits that occur with TBI, and thus help the physician make a rapid and accurate diagnosis.”

- If subsequent studies are able to validate these results, we may soon see changes to the NFL concussion protocol wherein NFL teams require players suspicious of having suffered a concussion to be evaluated using similar eye-tracking algorithms by watching short segments of films in video booths similar to on-the-field replay booths used by NFL officials. The more interesting question may be which music video players such as Marshawn Lynch or my good friend and former teammate, Haloti Ngata will watch when being evaluated for a possible concussion, will it be, “Under the Sea” or “I Just Can’t Wait to be King?”

- As soon as the NFL begins using eye tracking tools to screen for concussions, collegiate and high school athletics will be soon to follow, which will stand to benefit many student-athletes who like me, may now dream of a career in professional sports, but will soon realize their brain may be their best asset, helping trainers, parents, and student-athletes enjoy athletics while still protecting their brains from concussion-related sports injuries.